In 2017, a Boston terrier named Lucky became the first client-owned dog to receive a partial corneal transplant to restore his vision in one eye. Although the transplant was a success, it did come with challenges—which inspired a team of Johns Hopkins biomedical engineering students and alumni to develop a device to make it easier for surgeons to perform partial corneal transplants on dogs.

Using the device, veterinary ophthalmologist Micki Armour has since performed 18 partial corneal transplants at Friendship Hospital for Animals in Washington, D.C. “This device simplifies and streamlines our ability to provide this service to our canine patients,” says Armour, who is now training other veterinarians from around the world to perform the surgery.

The genesis for this advance goes back four years, when Akash Chaurasia, then a first-year student at the Whiting School, was part of an eight-person design team that began researching problems in the human ophthalmology field that could be solved through innovation. The team learned that Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty, a type of corneal transplant that can produce excellent outcomes for human patients, is also challenging for surgeons to perform. One of the primary issues is that the donor cornea’s thin, fragile tissue can roll up after being injected into the eye, leaving surgeons with the difficult task of unrolling the tissue without damaging it.

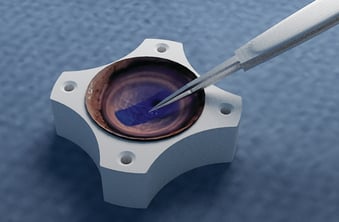

Working with Allen Eghrari, an ophthalmologist at Johns Hopkins’ Wilmer Eye Institute, Chaurasia and his classmates created a device to help surgeons address this problem. After folding the corneal tissue in a specific manner, the tissue roll is loaded into the student-designed device, which is then provided to the surgeon. When the surgeon injects the graft into the recipient’s eye, it unrolls instead of curling up. In 2017, Chaurasia, along with several other students and alumni, co-founded Treyetech, a startup company, to bring the device to the market. As of February, it was awaiting FDA approval.

But the team also wanted to help other potential recipients. “During our research, we learned about the veterinary market,” Chaurasia says. Eghrari told them that the field of canine ophthalmology was ripe for innovation. The students zeroed in on developing a device to help enable partial corneal transplants to dogs with corneal endothelial dystrophy. A condition similar to Fuchs’ dystrophy in humans, it is marked by a declining number of endothelial cells, which pump water from the cornea to keep it clear. With fewer cells, a dog’s cornea becomes cloudy and covered in a blue haze, vision loss can occur, and painful ulcers may develop, potentially necessitating removal of the affected eye. Veterinarians have been able to treat the symptoms, but until now, there hasn’t been an easy way to perform a partial corneal transplant to restore vision.

“That’s the problem the team had to solve,” says Steven Solar, a sophomore working on the canine project.

Along with Chaurasia and Solar, sophomore Batya Wiener, first-year Satya Baliga, Conan Chen ’18, Eric Chiang ’18, and Kali Barnes ’18 created the device, of which there are two versions: the Luna inserter and the Lucky inserter. Although it has been scaled for dogs’ corneas, which are larger and floppier than those of humans, the device works like its counterpart for humans. To address the challenge of the graft curling up in the eye after injection, the team leveraged a trifold technique—the same one used with the device for humans—in which surgeons fold the graft against the way it naturally curls before inserting it into the device. “Then when you put it in the eye and let go, it will naturally open up and flatten out, which can simplify the surgery,” Solar says. The endothelial cells also face one another inside the device, which prevents them from getting lost—the potential challenge with Lucky’s transplant —when they are inserted into the eye.

Chaurasia’s proudest moment was when he saw a video of Armour using the device to insert a graft into a dog’s eye. “Sometimes you lose sight of the bigger picture because you’re staring at Google Docs or reading literature all day,” he says. “Then you see your device actually having an impact. That was a real moment for me.”

– Jennifer Walker