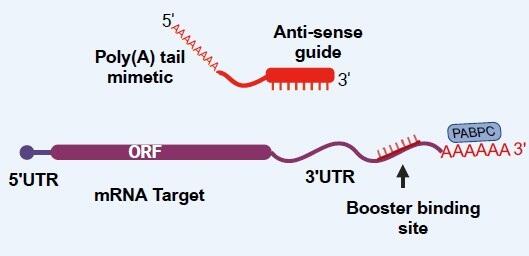

Johns Hopkins Medicine laboratory scientists say they have developed a potential new way to treat a variety of rare genetic diseases marked by too low levels of specific cellular proteins. To boost those proteins, they’ve created experimental versions of a genetic “tail” that attaches to so-called mRNA molecules that churn out the proteins.

A report on the researchers’ proof-of-concept work on laboratory-cultured cells and mice appears in the March 11 issue of Molecular Therapy—Nucleic Acids and could pave the way for therapies for diseases in which one copy of a person’s genes is missing or altered so that only half the amount of protein is made. Such disorders, although rare, include some forms of cancer, and immune system and neurodegenerative disorders, including SYNGAP deficiency, which results in learning disabilities and autism features in children.

There are more than 300 such conditions (haploinsufficiency diseases) and some also lead to developmental delays.

“Our research began as a way to help families find new treatment options for these diseases, in addition to gene editing therapies that are being studied now,” says Jeff Coller, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of RNA Biology and Therapeutics at Johns Hopkins University and professor of biomedical engineering, molecular biology, and genetics at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Protein booster exploits a natural protein-making system

The research team built its therapy from systems found in nature, in which each parent contributes half their DNA to a child. DNA contains genes that are turned on and off to produce cellular proteins that make our body function properly. If one parent’s gene copy is missing, or if it contains a mistake, the other parent’s gene copy is the only source of that protein, so about half of the protein level in the cell goes missing.