Two days into a four-week immersive pre-college experience at Johns Hopkins this past July, one of the high school participants remarked that a specific cell therapy used to treat cancer could have implications for HIV treatment. Jess Dunleavey, a lecturer in the Johns Hopkins Department of Biomedical Engineering, reacted in awe.

“I just watched a 16-year-old make a scientific connection that I’ve observed graduate students not create,” Dunleavey said. “The fact that we have students here doing that, and that’s who we brought in…I’m loving having those students here.”

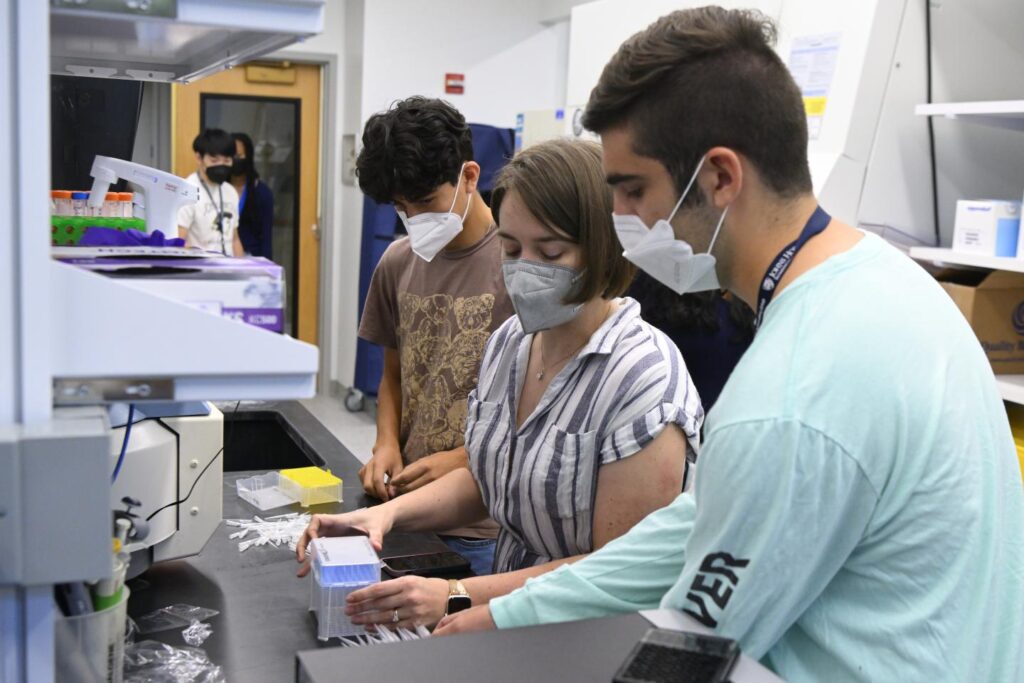

The Immersive Summer Program for Education, Enrichment, and Distinction in Biomedical Engineering, or ISPEED, aims to provide a hands-on experience for exceptional high school students who are from backgrounds underrepresented in science and technology fields. The program focuses on three key areas: life sciences, quantitative sciences, and health care design—each of which are areas of focus of the Johns Hopkins Department of Biomedical Engineering, which sponsors the program. The summer experience provides an insider’s look at what it’s like to be a biomedical engineer working in the nation’s top-ranked biomedical engineering department.

The program is fully funded for participants to reduce the barriers for their attendance in the hopes of making it an accessible option for students from any background. This year’s cohort included first generation and low-income students, students from underrepresented communities, and underserved populations from across the country, with about 50% coming from Baltimore or Washington, D.C.

In addition to the academic offerings of the program, ISPEED also offers student participants mentorship, financial aid advising, and guidance on curating a college application. Michael I. Miller, a professor and director of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, said the program aims to build connections between prospective college students and STEM programs in order to increase the diversity of incoming classes.

“Inclusive excellence is one of the core values of Hopkins BME,” Miller said. “As engineers, we are creators, we are disruptors, and we are innovators who are engineering the future of medicine. It is vital that we have people with different perspectives and lived experiences in our laboratories and in our classrooms so we can continue to create health care solutions and new ways of thinking about our world.”

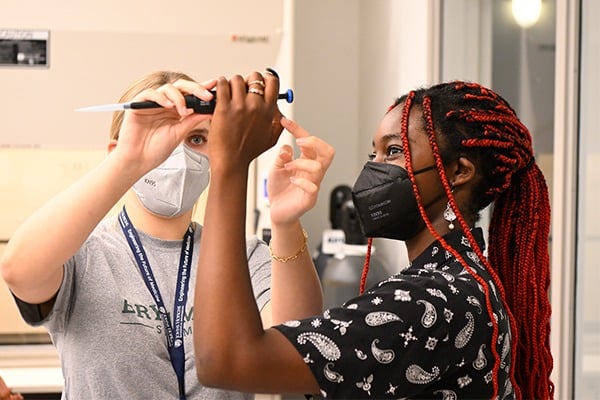

The program is unique in its project-based curriculum. Students are taught the fundamentals of design thinking to solve problems the way engineers do. The program’s first year curriculum focuses on finding health care solutions related to cardiovascular systems—bringing together the biology, quantitative coding, and design thinking to solve problems. In the first week of this summer’s cohort, students took their own EKGs, and later wrote code to predict the heart rate beat per minute from their individual EKGs, while also learning about treatments for hypertension. Dunleavey led a series of wet labs for the program, where students looked at living cells and took multicolor fluorescence microscopy images of the cells—all with the goal of immersing the students in the Hopkins BME world.